|

|

|

|

|

Ritual to Recognition: Modern Visual Language of Ram Singh Urveti

Yash Sakla 1![]() , Dr. Suman Pandey 2

, Dr. Suman Pandey 2![]()

1 Research Scholar, Faculty of Design, Gujarat Law Society University, Gujarat, India

2 Assistant

Professor, Faculty of Design, Gujarat Law Society University, Gujarat, India

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

The entry of tribal visual culture

into the world of contemporary art, as exemplified by Ram Singh Urveti, a

groundbreaking artist of the current Gond art scene, presents a striking

example of the transformation of traditionally community-oriented, ritualistic

visual culture into the realm of contemporary art. Drawing on the oral

tradition and cosmological narratives of the Gond Pradhan community, Urveti's work reimagines ancestral myths and fables

through intricate linework, symbolic animal images, and natural landscapes.

The paper will discuss how he shifted his mode of collectively telling

stories to being an independent artist, starting with his youthful

partnership with Jangarh Singh Shyam, and to his

maturity as a renowned artist who is honored globally. The paper challenges how the art of Urveti navigates across the domains of tradition and

modernity by visually offering a cultural examination of the use of selected

works. This paper is informed by the theory of cultural memory Assmann (1995), visual performativity Mitchell (2005), and the theory of

indigenous aesthetics to analyze how his paintings not only become the

repository of Gond cosmology but also become a part of indigenous visual

agency. There are particular details focused on the interrelation between

metamorphosis and mythology in his works, which are presented at exhibitions

in such institutions as Bharat Bhavan, Sarmaya Arts

Foundation, Ojas Art Gallery, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This paper, by placing the practice of Urveti in the broader context of decolonial visuality and

vernacular modernism, helps supplement the academic knowledge around the idea

of tribal art with notions outside of ethnographic perspectives. It puts into

the foreground the distinct visual discourse created by Urveti

that, as a transnational hybrid, mediates between the legacy of knowledge

systems and the contemporary global field of art. |

|||

|

Received 18 April 2024 Accepted 19 August 2025 Published 22 August 2025 Corresponding Author Dr. Suman

Pandey, suman.fineart@gmail.com DOI 10.29121/ShodhShreejan.v2.i2.2025.29 Funding: This research

received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial,

or not-for-profit sectors. Copyright: © 2025 The

Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License. With the

license CC-BY, authors retain the copyright, allowing anyone to download,

reuse, re-print, modify, distribute, and/or copy their contribution. The work

must be properly attributed to its author.

|

|||

|

Keywords: Indigenous Art,

Visual Narrative, Gond Painting, Tribal Modernity, Myth and Memory |

|||

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last decades, the Indian indigenous art has experienced a radical transformation both in reality and in perception. Tribal art Once placed on the fringe of ethnographic concern or museum folklore; tribal art is currently coming to be known as a legitimate and dynamic approach to contemporary visual language. The appearance of individual tribal artists as visual authors and cultural agents has disturbed long-standing binaries involving tradition/modernity, ritual/representation, and anonymity/authorship. Ram Singh Urveti, a revolutionary Gond painter, whose transformation from teller of village-based narratives to international art festival show is an epitome of this epistemic change in the representation, protection, and performance through art representing indigenous systems of knowledge.

Urveti was born in the Dindori district of Madhya Pradesh and comes from the Gond Pradhan community, where storytelling, song, and image have long survived as interdependent forms of cultural transmission. Studied with legendary master of Bhopal School, Jangarh Singh Shyam, Urveti began his career in mural work but subsequently developed his elaborate visual style of organic symmetry and mythic narrative combined with symbolic metamorphoses of flora and fauna. His artworks do not just depict Gond cosmology but re-create it. A sharpened graphic language through the use of linework and form, Urveti brings to life a visual cosmogenesis that draws on local ontology but is sensitive to the context of the exhibition.

This paper will chronicle the artistic development of Ram Singh Urveti using some of the works presented in the exhibition collection of the Ojas Art Gallery and critically interfacing with several available theories such as the theory of cultural memory by Jan Assmann (1995), theory of visual performativity (2005) by W.J.T. Mitchell, the theory of vernacular modernity in Indian tribal art etc. It will seek to show that Urveti is not only another practice of continuing Gond traditions but rather a reproduction of indigenous visuality in communication with artistic discourses of contemporary art.

Through this, the paper investigates the transformation of the identity of the tribal artist from a ritualist to a cultural writer, in addition to reflecting on how Urveti performs as a memory site, a site of agency, and a site of transformation. His paintings are not unchanging pictures but theaters of performance where the myth turns into methodology, the tradition into a story, and the image into speech. Set in the extended context of decolonial aesthetics and indigenous futurisms, the work of Urveti forces the positioning of tribal art as not an outdated victim of the past, but a relevant agent in the plural future of the present.

2. Literature Review

Academic study of Indian tribal art has undergone a slow transmutation in which it became interdisciplinary and critical by involving aesthetics, identity politics, and postcolonial discourse. Early explorations, describing indigenous art forms, such as Verrier Elwin (1951) and Goetz (1959), were early contributors towards documenting indigenous art forms, but the discussion of tribal art emerged through a romanticized, primitive paradigm concerning its functional or ritualist purposes within insulated groups. These texts saved important information about the culture, but they did not always acknowledge the artistic power and aesthetic independence of the artist.

Ram Singh Urveti is an artist who comes out of a Pardhan Gond tribal art tradition of Madhya Pradesh, in which practice, visual culture was unified within ritually applied wall and floor painting that is anchored in the seasonal rhythms and communal ceremonies. According to the article by Archana Rani titled The Journal of Commerce and Trade, Urveti is placed in the context of Jangarh Singh Shyam, whose inventions introduced Gond visual aesthetics into transportable mediums like paper and canvas and opened the possibility of their entry into galleries and the art market Rani (2019). What can be read in these fluctuations between ephemeral ritual surfaces and lasting, commercializable objects is the ritual-to-recognition shift that forms the substance of Urveti practice.

The paintings made by Urveti are known to have the dense infill of arrowheads, rounded figures, and a recurring arboreal collection, particularly the Tree of Life. Such components, which are defined by the MAP Academy, are used as decorative patterning as well as symbolic pegs of cosmological narratives (“Ram Singh Urveti”). The research by Archana Rani indicates the tendency of Urveti towards minimum figural density where the crowding is substituted by the rhythmicality linearities, which form a meditative ornamental space (Rani 41-47).

The shift in the tribal art discourse was more pronounced in the late 20th century when Jagdish Swaminathan came up with pioneering curatorial and institutional work at Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal. Swaminathan defended the hierarchy of division between the high level of art or fine art and the folk art by bringing out tribal artists like Jangarh Singh Shyam on the same level as modern Indian artists. He explained that tribal artists had similar visual intelligence, as well as metaphoric depth, to urban artists. These movements led to the concept of the vernacular contemporary as developed by Jain (2010), who considered the tribal artists to be the agents in the redefinition of the aesthetic standards, frequently simultaneously manipulating between the tradition and modernity driven by the market.

Nonetheless, although a lot of literature is available on Jangarh Singh Shyam and his close successors, others, such as Ram Singh Urveti, should be discussed academically more often than before. Urveti, an artist who started working with Jangarh, has shown a unique visual language that gives as much weight to the Gond myth as thematic innovativeness in the modern style. His paintings are frequently zoomorphic, dealing with metamorphic animals, enchanted forests, and intertwined worlds, with some resonance of the stratified narrative of his people, but drawing upon the closed and individualized authorship.

The given paper aims at filling that gap by applying to the work of Urveti the three key lenses: the semiotic triad presented by Roland Barthes (denotation, connotation, myth), the concept of cultural memory introduced by Jan Assmann, and the concept of visual performativity provided by W.J.T. Mitchell. These structures permit a more developed interpretation of the way that in the imagery of Urveti, which is not merely an aesthetic art object, we are presented with cultural writings that evoke memory, myth, and the rights of the eye.

Furthermore, the issue of selling the tribal art opens a question relative to authenticity, author, and morality of representation and sale in city galleries and the worldwide market. These issues have been discussed by such academic authors as Ruth B. Phillips and Nicholas Thomas in the larger scope of the world. As a result, they mention how indigenous art can exist in the paradox of being cultural and at the same time circulated by commerce. Urveti has indeed exhibited with such galleries as Bharat Bhavan and the IGNCA, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where his work exists in the in-between of tradition and transnationality.

This literature review will set the background to examine the practice of Urveti in the light of the developing discourse of indigenous aesthetics, vernacular modernism, and decolonial visuality, constructing the core of the understanding of his role in the modern tribal art movement in contemporary India. It emphasizes the necessity of more incisive scholarship in the study of artists who are much community-based yet extend the epistemological and aesthetic horizons of Indian art.

3. Methodology

This study uses the qualitative and interpretive research approach based on the analysis of visual culture. The main source of information is the collection and exhibition records of Ojas Art Gallery, where the artworks of Ram Singh Urveti have been exhibited most of the time. The secondary sources used are academic writings, exhibition catalogs, artist interviews that can be found in institutional collections, and publications.

There are three major theoretical approaches, which are used in the study:

The theory of semiotics was created by Barthes (1977): breaking down the artworks into three parts, namely, denotation, connotation, and myth.

Assmann (1995) Cultural Memory Theory: realizing ways in which the artworks of Urveti should be seen as containers of learned Gond cosmology and ecology.

Visual Performativity by Mitchell (2005): the meaning of the artwork as a representation understood also as a performative act of asserting the cultural identity and agency.

Through such lenses, certain artworks are detailed to interpret the transformation of a ritualistic construction of the community to the presently authored and visualized sense of sight.

4. Analysis

4.1. Devta by Ram Singh Urveti (2003)

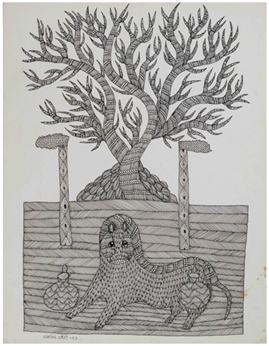

Figure 1

· Denotation (Barthes): A human-like person having the features of an animal, buried under a tree whose branches are patterned. The setting creates an impression of a holy place surrounded by two vertical poles.

· Connotation: This character can be a forest guarding god or a spiritual guardian, as this animal's body is a hybrid and mysterious. The tree was a symbolic signifier of sacredness and continuity, coupled with being a natural element.

· Myth: The art mythicizes nature in deifying and personifying it. It echoes Gond cosmology, where the nature and gods are not separated, and species connections have permeable boundaries.

· Assmann: Cultural Memory: There is also a certain ecological wisdom of the tribe that is close to the Earth here in the painting: trees, as gods, animals as spiritual supporters.

Generational memory of the work speaks that nature is not just a livelihood but a holy sibling.

Performance of Visuality (Mitchell): Not mere representation, but in itself, this sterilization acts in the name of veneration. Urveti is carried out in the Gond ontology through a representational nature as an anthropomorphic object that merges the form of nature and spirit.

4.2. Devi (2020)

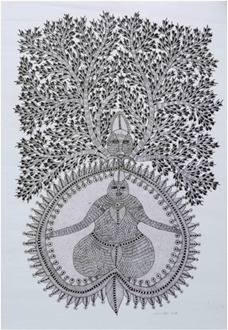

Figure 2

· Denotation (Barthes): A woman goddess is in the center, displaying a large, symmetrical tree sprouting out of her head; the part that comprises her body displays the aspect of a mandala. Then above her is still another face, coming in continuation of the tree.

· Connotation: It reminisces about fertility, maternity, and divine femininity. The two-sided facades and the circular structure refer to birth, rebirth, and cosmic oneness.

· Myth: It is a female-focused cosmology in which the goddess is not the supplement to a male god but the origin of life and the state of balance in the Universe. The myth disobeys patriarchal dualities.

· Assmann Cultural Memory: Devi is remembering the Earth as mother, and this idea beats in the heart of the tribal and pan-Indian trends. The tree sprouting out of her head supports the fact that the body is the source of the expansion and wisdom of the world.

· Mitchell (Visual Performativity): The image is a ritual of performance of the centrality of the female in the workings of the ecology and the cosmos. The painting is a kind of holy mandala that can inspire respect and memorization.

4.3. Sheshnaag Dharti Mata (2023)

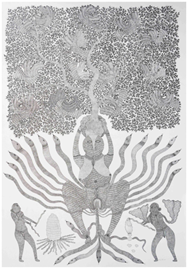

Figure 3

· Denotation (Barthes): A goddess with snake-like sprouts into a tree canopy. On both sides of her are two humans’ beings, one aiming an arrow and the other holding some shrub or object of the ritual.

· Connotation: An amalgamation of serpent, tree, and goddess, this is a symbol of fertility and a symbol of primordial strength. The leaf and the bow present two opposites, destruction and caring, and even worship and a threat.

· Myth: This picture tells the mythical story of the Earth Mother who is guarded by the serpents, which is attacked by forces outside, but is based on the strength of self-generation. She is the tree, the earth, the revolt.

· Assmann, Cultural Memory: This image recalls and re-performs the gendered wisdom of indigenous people, earth, and serpent as divine feminine. It is based upon primitive serpentine worship and matriarchal fables inherent in tribes.

· Mitchell: Visual Performativity: The goddess does not act: she acts power. Her body is a warrior zone, a native cathedral, and an environmental womb. The painting is proactive, and it presents female agency against violence.

4.4. Devi Bhadita (1999)

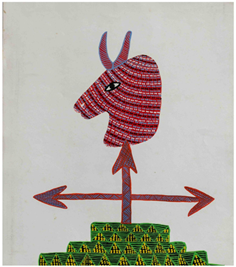

Figure 4

· Denotation (Barthes): Stylized red decorated goat-head that has arrows stemming out of its neck and nose held on top of a green pyramid consisting of triangular shapes.

· Connotation: The directions marked by the arrow indicate forced moving, exile, or attack. Red and intense head could be the visual representation of a raped goddess, a persecuted spirit, or a dispossessed creature.

· Myth: This artwork contravenes the traditional imagery of God. It is a myth of distortion when the goddess becomes injured or dislocated. Devi appears, but she is transformed; she is mute and abstract, the sign of trauma.

· Assmann Cultural Memory: It may be pointing to an unseen or a forgotten story in which the goddess is deprived of a voice and a body. It refers to displacement in history, of women, of animals, of gods.

· Mitchell: Visual Performativity: Instead of proclaiming power, this painting enacts sorrow and opposition in shape and color. It is criticism, but deadly if unspeaking. The fact that there is no full body is the loudest talk!

5. Thematic Connection and Discussion: Spatial Ecologies of the Feminine in Gond Art

The chosen pieces of the collection of Ram Singh Urveti (in the collection of the Ojas Art Gallery exhibition archive) create a complex spatial and semiotic mesh in the context of which Gond cosmology, women's power, and ecological memory unite. In the collection of works, researchers get to see not simply the images of gods or mythological themes, but a kind of visual-spatial action in which the body, nature, and the ritual space are closely inscribed in one another. In this part, we will look at how space in these pieces of art turns into an area of performance where the self is realized, a storehouse of the cultural memory, and into a heuristic region of sound and resuscitation.

In Devta (2003), nature as a divine protagonist comes out clearly in the way the composition revolves around trees that are not utilized as the background. These shapes of denotative functions, the tree, the animal-figure, the two pillars protecting each side, are a good example of the symbolic resonance which they are made to recount: protection, rootedness, continuity of the cosmos. In the model developed by Roland Barthes, the mythic level comes out as in the case of the Gond who believe in the deities in the forest that represent the spirit of the land. Positioning of the tree in the visual center of the composition, with symmetrical tree limbs and repetition, supplies the sacred geography of space, setting up the worldview of the Gond and experiencing the spaces within a forest as locations to live, imagine, and worship. This picture executes what W.J.T. Mitchell calls visual performativity: it both portrays the deity and renders his presence, line of defense over soil, sentient and spirit.

In Devi (2020), the goddess character is not presented as a subordinate to some male god, but as the cosmic creator. Instead, the body of the Devi constitutes a mandalic shape, one of the most recurrent forms of symbolism of the totality and the spiritual order in the Indic visual traditions. Yet, in this case, the mandala is not an abstract concept; it is merged with the tree of life as it grows out of her head. This space fusion is crucial to reading through the theory of cultural memory by Jan Assmann. The Devi is a mnemonic vessel and also a symbolic maker of ecological continuity. She embodies a memory bearing the manifestation of creation, the forest, knowledge of gender, and spiritual equilibrium. The stacking image of the face (both in and out) is reminiscent of reJohn Davieson (2003); this lies in the fact that the way the image is presented, the faces are stacked on top of each other or sort of layered, is a reiteration of rebirth and the multiple identification of the self. She dismantles her image with space dualities: land and the sky, roots and canopy, past and future. With this, she is transformed into cosmos and cartography. The arranged positions between the actors and the background also promote ecological embodiment in Mata (2023). Devi, with numerous limbs, turned into serpents, appeared from a thriving tree canopy, where visually her consciousness and breath embrace the foliage, plants, and animals alike. The figures surrounding are in interactive poses; one holding a bow (emblem of violence or defeat), the other seems to be holding on to something which appears to be some form of ritual goods (act of admiration). This contradiction inscribes a performative negativity in the context of the image. The goddess of the earth is not helpless; her body turns into a war zone as well as a place of refuge. The myth Barthes refers to in this context mobilizes the archetype of woman-as-earth, life is born, endures, is in danger, and never ever gives up her power. Culturally, this is reminiscent of the Gond view of Dharti Mata not as an icon, but as an animate geography, besieged on the one hand by external forces of a more colonial, patriarchal, and industrial nature, but hot with petitions and mythic revolt.

A completely different spatial aesthetics is brought up by Bhadita (1999). Here, the abstracted red head of an animal-like Devi is placed in the directional arrows, which means dislocation or the given trajectory. The reduced visual vocabulary is not subtle or distant but advanced: there are no trees, no mythic feel, only symbolism. This work effectuates a semiotic break, since visually it abandons the organicity of the motifs of earlier works, in favor of presenting a disembodied, fragmented iconography. The myth in this case is the myth of disruption- possibly it is the effacement of feminine structures by their kind to sacred ecosystems or the destruction of modernization to native cosmologies. The arrows hint at exile, pointing off in divergent directions, which indicates epistemic, not only physical, displacement. Culturally, that picture expresses a loss constitutive of the spatial disjuncture of goddess and land, self and sacred. The loss of the full body as such is visually a performative act, a space that is emptied precisely to turn invisible loss visible.

Collectively, the works would spatialize a feminine map of memory and resistance. The semiotics of things is such that trees, bodies, animals, and symbols are not dislocated: They are inseparably enclosed within a semiotics of rituals producing a tribal world view in which knowledge is inseparably embodied and spaces within a semiotic. The image turns out not merely to be a location of the seeing but a location of performative continuity, as the drawing, the remembering, and the believing come together.

Moreover, patterning, repetition, and, ultimately, symmetry, which are usually the classical features of Gond visual language, do not simply perform a decorative role. They are labors of memory: the line, the dot: a remembrance, a strand woven into the tapestry of wisdom in the family history. With these style decisions, the geography of the feminine becomes liminal, moving between what is real and what is in-between: land, narrative, body, and opposing radiation.

To sum it up, the artworks by Ram Singh Urveti turn out to be aesthetic ecologies since spatial patterns call into play the mythic time and enact cultural identity and resist the erasure through the visual insistence. Engaging Barthes, Assmann, and Mitchell enables us to interpret them not just as pieces of art but as visual documents of memory and livelihood that re-code back indigenous ways of knowing onto the modern-day canvas.

Certainly. In the following, I have written the conclusion to your research paper on the topic, Ritual to Recognition: Modern Visual Language of Ram Singh Urveti, in a scholarly language appropriate to your semiotic, cultural memory, and performative constructs and frameworks:

6. Conclusion

The artistic development of Ram Singh Urveti, the tribal ritualization of images to a formally identifiable modern language, is a magnificent cultural reassertion as well as a visual transformation. As semiotic analysis, performative interpretation, and cultural memory theory elucidated in this paper showed, the Urveti artworks are far beyond being the types of Gond mythology, which they tend to represent as a collection of simple textual tropes or visual illustrations; Urveti works are complex visual texts, in which their identity is performed, their erasure is resisted, and the indigenous knowledge systems are recontextualized into modern art discourse.

In every painting, there is a complex exchange between the formal and ceremonial gesture and the contemporary acknowledgement, and the utilization of classical gestures, such as trees, gods, and animals, divulge into glowing symbol--in one sense referring to the divine, in another sense, evoking a sense of ecophilia, and, in a more mythic rendition, reboot of a repressed cosmology. Spatial aesthetics Urveti operates beyond decorative folk patterns as they appear as acts of memory, as modes of performance. Line and form in such contexts act as stores of histories, proscriptions against homogenization, and embodied means of expressing an indigenous epistemology of land-based spirituality.

As apparent in the cosmographical aspect of the goddess as the Tree of Life to the nerve-wrecking abstraction of displacement in Devi Bhadita, the visual language of Urveti can also be considered as a critical deformation of tribal authenticity in the name of global viewability. The very logic of his practice reads as a pathway in which purpose has not been lost and ritualized, but lost and translated in a different, often unrecognizable language that, nevertheless, can be seen, in the logic of his word, to be counted as such.

Accordingly, the work of Urveti lives up to a contemporary tribal modernity, not parasitic either upon the Western-European pattern of modernity or limited by an ethnographic nostalgia. Rather, it creates a self-sufficient field of aesthetics in which ritual memory, visual sovereignty, and cultural survival co-exist. This shift to recognition is not only a personal development of the artist but also indicates the move that indigenous art has made in terms of claiming itself as an important voice or claim within modern and global visual cultures.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

REFERENCES

An in-Depth Exploration of Bhil Art-Inspired Design in Contemporary Textile Products. (2024). ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, pp. –.

Assmann, J. (1995). Collective Memory and Cultural Identity. New German Critique, (65), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.2307/488538

Barthes, R. (1977). Image-music-text (S. Heath, Trans.). Fontana Press.

Bharat Bhavan. (n.d.). Exhibitions and Permanent Collections.

Bhil art: A Critical Literature

Review on Tradition, Expression, and Cultural Preservation. (2024, April). Eduphoria:

An International Multidisciplinary Magazine.

Elwin, V. (1951). The Tribal Art of Middle

India. Oxford University Press.

Enhancing Traditional Craftsmanship: Impact of Training on Mandana, Bhil, and Gond Artisans. (2025). Proceedings IMASEE.

eTribal Tribune. (2025, August 15). Ram Singh Urveti: A Profile of an Artist.

Goetz, H. (1959). The Art and Architecture of India. Oxford University Press.

IGNCA. (n.d.). Tribal and Folk art Archives. Retrieved from

Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. (2025, August 15). Ram Singh Urveti – Gond artists of Madhya Pradesh.

Jain, J. (2010). Living Traditions: Contemporary Folk Art from India. Mapin Publishing.

MAP Academy. (2025, January 25). Ram Singh Urveti. MAP Academy Encyclopedia of Art.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2005). What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226245904.001.0001

Ojas Art. (n.d.). Exhibition Archive and Catalogue: Ram Singh Urveti. Retrieved from

Ojha, S. (2021). The Re-Imagining of Tribal Art in India: A Study of Jangarh Singh Shyam and His Legacy. South Asian Studies, 37(2), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666030.2021.1889795

Philadelphia Museum of Art. (2018). Painted Songs and Stories: The Hybrid Art of India's Gond Tribes [Exhibition notes]. Retrieved from

Phillips, R. B., & Thomas, N. (1998). Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American art from the Northeast, 1700–1900. University of Washington Press.

Rani, A. (2019). The Gond Painting of Prominent Artists (An Exploratory Study of Jangarh Singh Shyam, Ram Singh Urveti). Journal of Commerce and Trade, 14(2), 41–47.

Sarmaya Arts Foundation. (n.d.). Ram Singh Urveti: Artist Archive. Retrieved from https://www.sarmaya.in/artist/ram-singh-urveti/

Sethi, A. (Ed.). (2015). The Spirit of Gond: The Art of Jangarh Singh Shyam and His Legacy. Roli Books.

Swaminathan, J. (1987). The Perceiving Fingers:

Essays on the Art of Tribal and Folk India. Bharat Bhavan Publication Division.

Thomas, N. (1991). Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. Harvard University Press.

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© ShodhShreejan 2025. All Rights Reserved.